Propithecus coquereli

Coquerel’s sifakas (Propithecus coquereli) are delicate leaf-eaters from the dry northwestern forests of Madagascar. The sifaka of Madagascar are distinguished from other lemurs by their vertical clinging and leaping mode of locomotion: these animals maintain a distinctly vertical posture and leap through the trees using just the strength of their back legs. These long, powerful legs can easily propel them distances of over 20 feet from tree to tree. On the ground, the animals cross treeless areas just as gracefully, by bipedal sideways hopping.

The Malagasy name ‘sifaka’ comes from the distinct call this animal makes as it travels through the trees: “shif-auk.”

Zoboomafoo

The Duke Lemur Center was home to the most famous Coquerel’s sifaka, Jovian, a.k.a. Zoboomafoo: the leaping, prancing star of the PBS Kids show by the same name, hosted by brothers Martin and Chris Kratt. Jovian was a graceful, long-limbed co-star with cream and russet fur and bright, intelligent yellow eyes, who helped teach millions of children what a lemur is. Zoboomafoo aired 65 episodes in just over two years, 1999-2001, and continues in syndication. Learn more in the menu below.

About Coquerel’s Sifakas

Adopt a Sifaka

Want to learn more about sifakas AND help support their care and conservation not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Pompeia the sifaka through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur Program! Your adoption goes toward the $8,400 per year cost it takes to care for each sifaka at the DLC, as well as aiding our conservation efforts in Madagascar. You’ll also receive quarterly updates and photos, making this a fun, educational gift that keeps giving all year long!

Zoboomafoo

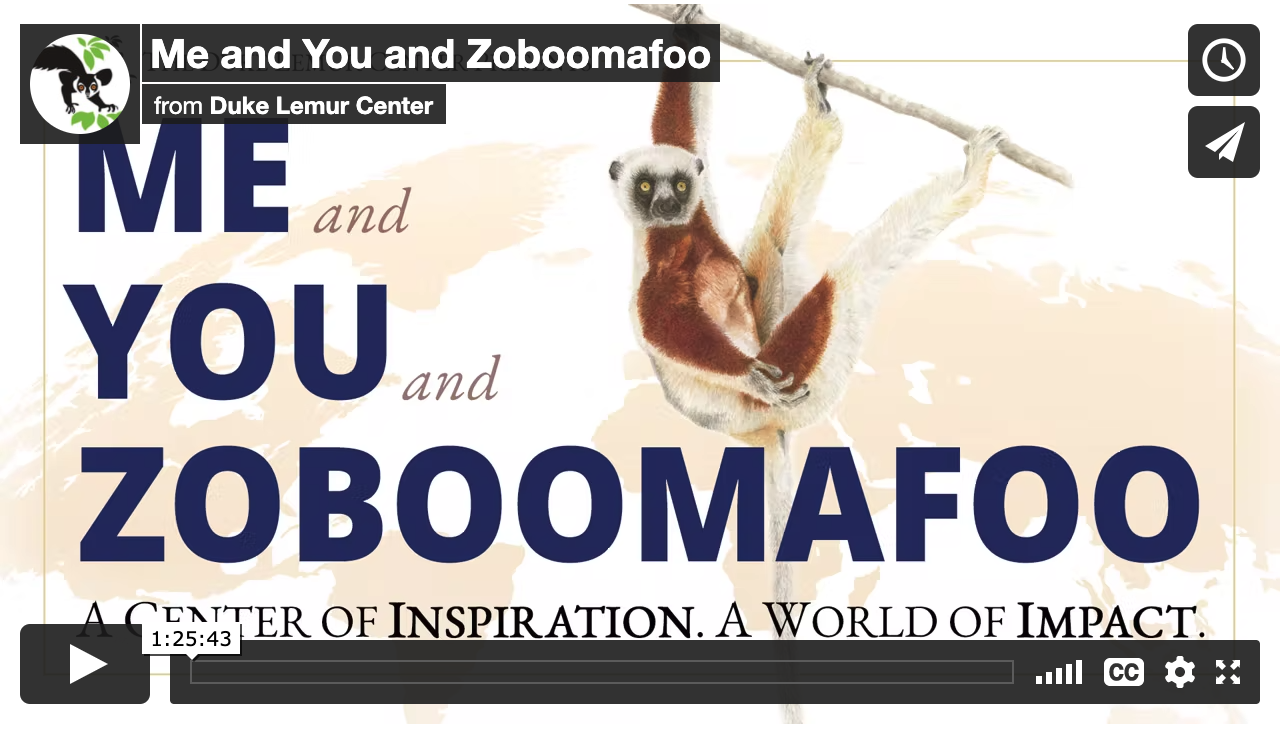

A Duke graduate (T'89) and former work-study student at the Duke Lemur Center, Martin Kratt is the co-creator of three popular children’s television shows about animals: Kratts Creatures, Zoboomafoo, and Wild Kratts.

Zoboomafoo in particular is dear to the Lemur Center’s heart. Starring Jovian, a much-loved Coquerel’s sifaka living at the DLC, the series aired 65 episodes in just over two years (1999-2001) and taught millions of children about lemurs and primate conservation.

Want to learn more? Watch Me and You and Zoboomafoo, a feature-length video adventure in which Martin shares stories of how his experience at the Lemur Center took him from being a Duke undergrad to an Emmy Award winner who’s introduced generations of children to lemurs and wildlife conservation. Of course, the film features LOTS of behind-the-scenes footage of the DLC’s lemurs, too, and even some retro Zoboomafoo!

Prefer print to video? In 2019, we had a chance to talk to Martin about Duke, the DLC, and the behind-the-scenes experience of filming Zoboomafoo. Read the interview on pages 30-33 of the DLC's annual magazine.

Quick Facts

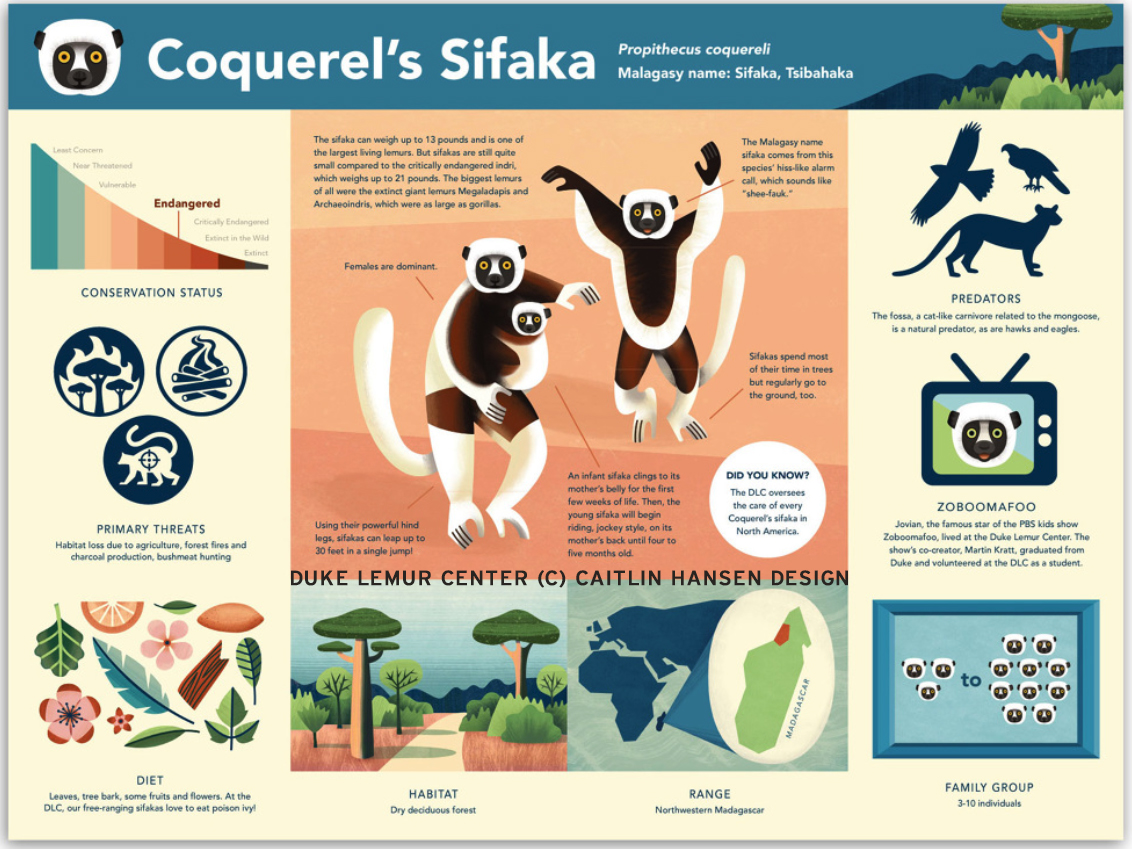

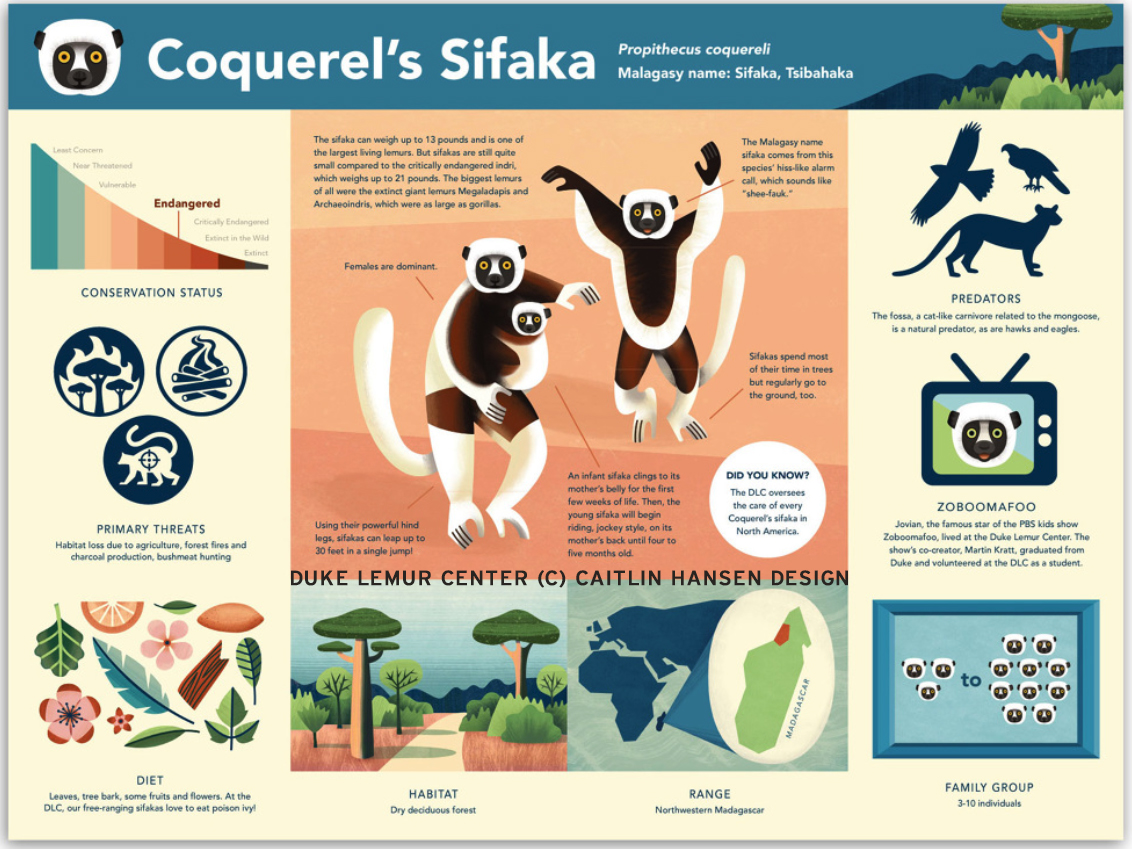

Sifaka infographic created for the Duke Lemur Center tour path (c) Caitlin Hansen Design. Click the image for a larger view.

Adult size: 8.1 - 9.5 lbs (3.7 - 4.3 kg)

Social structure: small family groups (three to 10 individuals)

Habitat: dry deciduous forest in northwestern Madagascar

Diet: leaves, flowers, bark, dead wood

Sexual maturity: two to four years

Mating: highly seasonal, infants are born in June to August in Madagascar and December to February in North Carolina

Gestation: 160 days

Number of young: one infant per season

IUCN Status: critically endangered

DLC Naming theme: Roman emperors, empresses, and consorts

Malagasy names: sifaka

Size and Appearance

Coquerel’s sifakas are the largest lemur species at the Duke Lemur Center, standing just under two feet (60 cm) tall as they vertically move through the forest. Adult sifakas weigh 8.1 - 9.5 lbs (3.7 - 4.3 kg).

In Madagascar, there are several species of sifaka, with fur patterns ranging from pure black to white with different patterns in between. Coquerel’s sifakas are mostly cream-colored, with deep rust-brown patches on each limb.

Diet

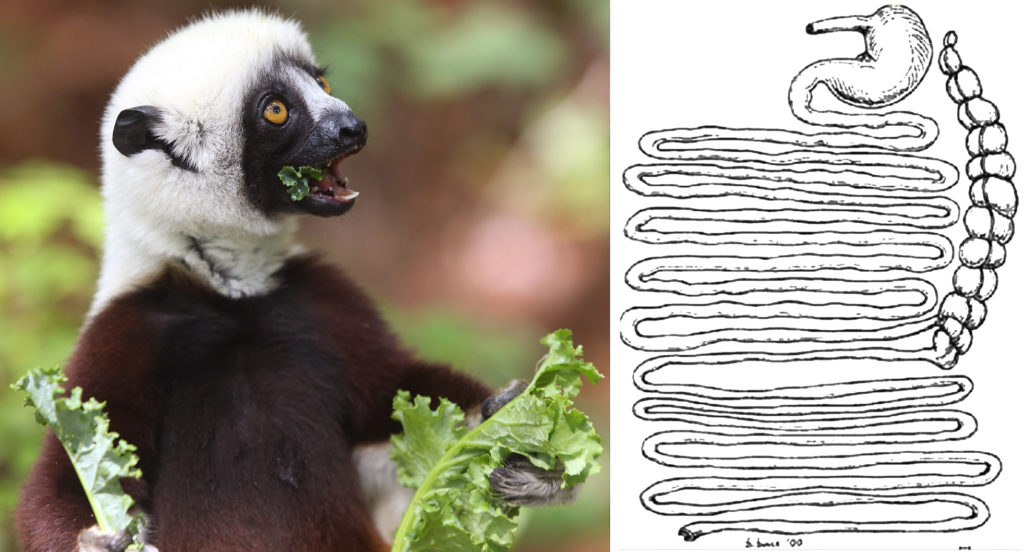

Above: Figure reproduced from Campbell et al. 2000. Description of the gastrointestinal tract of five lemur species: Propithecus tattersalli, Propithecus verreauxi coquereli, Varecia variegata, Hapalemur griseus, and Lemur catta. American Journal of Primatology. 52: 133-142.

Digestive system

Sifakas eat foliage and seasonal fruits, and their gastrointestinal systems are designed to optimize nutrient extraction from both. Sifakas have an elongated gut tract that is an astonishing 14-15x their body length, and food takes about 24-36 hours to go from eating to excreting.

Sifakas' small intestines are 9x their body length, which provides space to absorb fruit sugars and fats. Sifakas also have an enlarged cecum — in the figure above, the cecum is the structure that looks like a rattlesnake’s tail — which is another 1x body length. The cecum is essentially an overgrown appendix and the powerhouse of microbial metabolism. In the cecum, gut microbes ferment tough leaf fibers into nutrients, degrade plant toxins, release plant proteins from the leaf matrix, and synthesize vitamins not available in the lemurs’ diets.

Diet and feeding

Because of their extremely sensitive digestive systems, Coquerel's sifakas have specialized nutritional needs. As a species, they have a reputation of being very delicate and difficult to care for, and the Duke Lemur Center is one of the very few places that has succeeded in caring for and breeding them. So much so, in fact, that all sifakas in human care are on loan from, and managed by, the Duke Lemur Center.

Because of their sensitive digestive systems, the DLC's sifakas are fed multiple times daily – which mimics the feeding bouts wild sifakas have throughout the day and keeps our lemurs’ GI tracts operating similar to that of wild populations. As part of our feeding strategy, we distribute browse (leaves) to the sifakas every afternoon — even to our free-ranging sifakas. In the wild, leaves comprise about 40-60% of sifakas’ diet; so it’s clear that browse is important, and introducing native NC browse plants into our sifakas’ diets has proved hugely beneficial.

At the DLC, our animal care team harvests fresh redbud, tulip poplar, mimosa, and sweetgum for the sifakas every day during the warmer months. The sifakas' favorite species of plant to eat here in the U.S. is winged sumac, Rhus copallinum, which is high in the tannins and sap that the sifakas enjoy.

Every fall, our animal care team also harvests and freezes enough browse to feed the sifakas throughout the winter, when there are no fresh leaves to harvest. Winged sumac is the only plant that will freeze well, without disintegrating upon thawing. We fill seven large chest freezers with sumac harvested from many different sites around Durham and Chapel Hill.

(Note: The sumac that we grow and harvest is winged sumac, Rhus copallinum — not poison sumac, Toxicodendron vernix. Toxicodendron is the same genus as our poison ivy, which believe it or not some of our DLC sifakas in the forest enclosures like to eat!)

In Madagascar, Coquerel’s sifakas feed on young leaves, flowers, fruit, bark, and wood in the wet season, and on mature leaves and buds in the dry season. As many as 98 different plant species have been recorded in their diet. However, only 12 of these plants make up two-thirds of the diet.

Reproduction

Gestation and birth

In the wild, female Coquerel’s sifakas give birth to one offspring in mid-summer, after a gestation period of approximately 162 days. At the DLC, breeding occurs in late summer to early fall, and single infants are born in late winter to early spring.

Infants cling to their mothers’ bellies for the first three to four weeks of life. Then, the young sifaka will begin spending a gradually increasing amount of time riding, jockey style, on mom’s back. Infants continue to ride their mother’s back, if allowed, during times when they feel threatened until they are five months old. However, by the time the infants are three or four months old, mothers will begin to nip at them to encourage the infants to find an alternate method of transportation!

Young sifakas become sexually mature at around the age of 3.5 years.

Conservation breeding program

The Lemur Center’s colony of Coquerel’s sifaka is the most successful breeding colony in the world of this species or any species of sifaka, and the DLC owns and manages every individual in human care.

The DLC has been successful enough with our conservation breeding program to send Coquerel's sifakas to other AZA-accredited institutions, and many of these facilities have seen their own breeding success based on DLC husbandry guidelines.

Prior to 2021, all of these partner zoos here here in North America; but in summer and fall 2021, the DLC shipped eight Coquerel's sifakas to three European zoos, in an historic expansion of our Coquerel's sifaka conservation breeding program—marking the beginning of a new chapter in lemur conservation.

Behavior

Coquerel’s sifakas live in social groups of between three and 10 individuals, and the age and sex composition of the groups vary widely. Females are dominant to males, which gives them preferential access to food and their choice of mate.

A home range of between 10 and 22 acres is maintained by wild groups. However, within this area, a core territory of five to eight acres is utilized over 60% of the time.

Habitat and Conservation

As of 2018, Coquerel’s sifakas are classified as critically endangered in Madagascar and are threatened with increasing habitat destruction and the erosion of social customs against hunting this species. Learn more about the new IUCN Conservation Assessment for this species and others here.

The species is found only in the Ankarafantsika Nature Reserve and the Bora Special Reserve, and these dry, deciduous forests have both been damaged by yearly fires set by nearby farmers. Hunting of these animals by locals might occur in some areas, although in many parts of its range it is protected by taboo or fady.

Videos

The DLC is located on 100 acres in Duke Forest and is famous for its Natural Habitat Enclosures. Here, lemurs free-range in large tracts of forest and live in natural social groups, giving researchers and visitors the opportunity to observe the same behaviors, social structures, and age classes that would be observed in the wild.

Here, a family of four sifakas is caught on trail cam bouncing through their forest home.

Sifakas are featured in episode three of our FREE virtual tour series! In this adventure into the DLC’s Natural Habitat Enclosures, we’ll watch sifaka doing the things they do best—all while learning how we keep lemurs safe and healthy in their forested areas. Take a walk on the wild side with Pompeia, Francesca, and a couple of photobombing friends!

Me and You and Zoboomafoo is a feature-length video adventure—created by the Duke Lemur Center in celebration of World Lemur Day on October 30, 2020—co-hosted by Duke alumnus Martin Kratt, co-creator of Zoboomafoo and Wild Kratts! Through Martin’s story and so many others, Me and You and Zoboomafoo explores how one place, nestled in the forests surrounding the Duke University campus, can inspire a whole world of impact.

Martin shares stories of how his experience at the Lemur Center took him from being a Duke undergrad to an Emmy Award winner who’s introduced generations of children to lemurs and wildlife conservation. Of course, the film features LOTS of behind-the-scenes footage of the DLC’s lemurs, too, and even some retro Zoboomafoo!

If you’ve ever been curious about how we train the lemurs to voluntarily come in from their Natural Habitat Enclosures (NHEs), then check out this behind-the-scenes video! Lemur caretaker Melanie Currie calls to Coquerel’s sifaka mother/daughter duo Pompeia and Francesca using their auditory cue (two short whistle bursts) and a little extra verbal encouragement: "Come on, Pom Pom!" Pompeia and Francesca leap right into a self-contained fenced area within the larger NHE, to enjoy their meal.

To provide an extra reward for their voluntary cooperation, all free-ranging Coquerel’s sifakas receive their favorite food—shelled peanuts—on their “lock-up days” twice a week over the warmer months. You can see that Francesca barely reacts to Melanie shutting the doors—she's far too busy with her peanuts! Don’t worry, after they finished their meals, Melanie opened the doors so that Pompeia and Francesca could continue enjoying the forest!

How You Can Help

Send a lemur a present: You can send special treats to the DLC’s lemurs, as well as raw materials for us to construct special enrichment activities to keep them happy and healthy. Simply visit our amazon.com wishlist! In the image above, Pompeia's daughters, Francesca and Isabella, enjoy their new interactive feeders gifted to them from the wishlist - so fun!

Adopt a Coquerel's sifaka: Want to learn more about this species AND help support their care, not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Pompeia, a female sifaka, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur program! Adoption packages start at just $50.

Visit the Duke Lemur Center: The DLC is only partially funded by Duke, so we rely heavily on revenue from tours to help pay for lemur care and housing as well as our conservation work in Madagascar. So, something as simple and fun as visiting the Lemur Center—either virtually or in person—can help us help the lemurs!

Engage in conservation locally: Though it doesn't directly affect lemurs, the DLC also promotes local conservation. We encourage visitors to support local ecosystems and protect local habitats, similar to the way we're helping the local people in Madagascar preserve lemurs' natural habitat. A fun way to do this is to plant a local pollinators garden at your home or school. The DLC itself is incorporating a Monarch Waystation into its landscaping for the summer tour path in 2017. You can also stop using dangerous chemicals on your lawn, which might end up in lakes and streams and harm fish, frogs, and other animals.

Want to learn more about sifakas AND help support their care and conservation not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Pompeia the sifaka through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur Program! Your adoption goes toward the $8,400 per year cost it takes to care for each sifaka at the DLC, as well as aiding our conservation efforts in Madagascar. You’ll also receive quarterly updates and photos, making this a fun, educational gift that keeps giving all year long!

A Duke graduate (T'89) and former work-study student at the Duke Lemur Center, Martin Kratt is the co-creator of three popular children’s television shows about animals: Kratts Creatures, Zoboomafoo, and Wild Kratts.

Zoboomafoo in particular is dear to the Lemur Center’s heart. Starring Jovian, a much-loved Coquerel’s sifaka living at the DLC, the series aired 65 episodes in just over two years (1999-2001) and taught millions of children about lemurs and primate conservation.

Want to learn more? Watch Me and You and Zoboomafoo, a feature-length video adventure in which Martin shares stories of how his experience at the Lemur Center took him from being a Duke undergrad to an Emmy Award winner who’s introduced generations of children to lemurs and wildlife conservation. Of course, the film features LOTS of behind-the-scenes footage of the DLC’s lemurs, too, and even some retro Zoboomafoo!

Prefer print to video? In 2019, we had a chance to talk to Martin about Duke, the DLC, and the behind-the-scenes experience of filming Zoboomafoo. Read the interview on pages 30-33 of the DLC's annual magazine.

Sifaka infographic created for the Duke Lemur Center tour path (c) Caitlin Hansen Design. Click the image for a larger view.

Adult size: 8.1 - 9.5 lbs (3.7 - 4.3 kg)

Social structure: small family groups (three to 10 individuals)

Habitat: dry deciduous forest in northwestern Madagascar

Diet: leaves, flowers, bark, dead wood

Sexual maturity: two to four years

Mating: highly seasonal, infants are born in June to August in Madagascar and December to February in North Carolina

Gestation: 160 days

Number of young: one infant per season

IUCN Status: critically endangered

DLC Naming theme: Roman emperors, empresses, and consorts

Malagasy names: sifaka

Coquerel’s sifakas are the largest lemur species at the Duke Lemur Center, standing just under two feet (60 cm) tall as they vertically move through the forest. Adult sifakas weigh 8.1 - 9.5 lbs (3.7 - 4.3 kg).

In Madagascar, there are several species of sifaka, with fur patterns ranging from pure black to white with different patterns in between. Coquerel’s sifakas are mostly cream-colored, with deep rust-brown patches on each limb.

Above: Figure reproduced from Campbell et al. 2000. Description of the gastrointestinal tract of five lemur species: Propithecus tattersalli, Propithecus verreauxi coquereli, Varecia variegata, Hapalemur griseus, and Lemur catta. American Journal of Primatology. 52: 133-142.

Digestive system

Sifakas eat foliage and seasonal fruits, and their gastrointestinal systems are designed to optimize nutrient extraction from both. Sifakas have an elongated gut tract that is an astonishing 14-15x their body length, and food takes about 24-36 hours to go from eating to excreting.

Sifakas' small intestines are 9x their body length, which provides space to absorb fruit sugars and fats. Sifakas also have an enlarged cecum — in the figure above, the cecum is the structure that looks like a rattlesnake’s tail — which is another 1x body length. The cecum is essentially an overgrown appendix and the powerhouse of microbial metabolism. In the cecum, gut microbes ferment tough leaf fibers into nutrients, degrade plant toxins, release plant proteins from the leaf matrix, and synthesize vitamins not available in the lemurs’ diets.

Diet and feeding

Because of their extremely sensitive digestive systems, Coquerel's sifakas have specialized nutritional needs. As a species, they have a reputation of being very delicate and difficult to care for, and the Duke Lemur Center is one of the very few places that has succeeded in caring for and breeding them. So much so, in fact, that all sifakas in human care are on loan from, and managed by, the Duke Lemur Center.

Because of their sensitive digestive systems, the DLC's sifakas are fed multiple times daily – which mimics the feeding bouts wild sifakas have throughout the day and keeps our lemurs’ GI tracts operating similar to that of wild populations. As part of our feeding strategy, we distribute browse (leaves) to the sifakas every afternoon — even to our free-ranging sifakas. In the wild, leaves comprise about 40-60% of sifakas’ diet; so it’s clear that browse is important, and introducing native NC browse plants into our sifakas’ diets has proved hugely beneficial.

At the DLC, our animal care team harvests fresh redbud, tulip poplar, mimosa, and sweetgum for the sifakas every day during the warmer months. The sifakas' favorite species of plant to eat here in the U.S. is winged sumac, Rhus copallinum, which is high in the tannins and sap that the sifakas enjoy.

Every fall, our animal care team also harvests and freezes enough browse to feed the sifakas throughout the winter, when there are no fresh leaves to harvest. Winged sumac is the only plant that will freeze well, without disintegrating upon thawing. We fill seven large chest freezers with sumac harvested from many different sites around Durham and Chapel Hill.

(Note: The sumac that we grow and harvest is winged sumac, Rhus copallinum — not poison sumac, Toxicodendron vernix. Toxicodendron is the same genus as our poison ivy, which believe it or not some of our DLC sifakas in the forest enclosures like to eat!)

In Madagascar, Coquerel’s sifakas feed on young leaves, flowers, fruit, bark, and wood in the wet season, and on mature leaves and buds in the dry season. As many as 98 different plant species have been recorded in their diet. However, only 12 of these plants make up two-thirds of the diet.

Gestation and birth

In the wild, female Coquerel’s sifakas give birth to one offspring in mid-summer, after a gestation period of approximately 162 days. At the DLC, breeding occurs in late summer to early fall, and single infants are born in late winter to early spring.

Infants cling to their mothers’ bellies for the first three to four weeks of life. Then, the young sifaka will begin spending a gradually increasing amount of time riding, jockey style, on mom’s back. Infants continue to ride their mother’s back, if allowed, during times when they feel threatened until they are five months old. However, by the time the infants are three or four months old, mothers will begin to nip at them to encourage the infants to find an alternate method of transportation!

Young sifakas become sexually mature at around the age of 3.5 years.

Conservation breeding program

The Lemur Center’s colony of Coquerel’s sifaka is the most successful breeding colony in the world of this species or any species of sifaka, and the DLC owns and manages every individual in human care.

The DLC has been successful enough with our conservation breeding program to send Coquerel's sifakas to other AZA-accredited institutions, and many of these facilities have seen their own breeding success based on DLC husbandry guidelines.

Prior to 2021, all of these partner zoos here here in North America; but in summer and fall 2021, the DLC shipped eight Coquerel's sifakas to three European zoos, in an historic expansion of our Coquerel's sifaka conservation breeding program—marking the beginning of a new chapter in lemur conservation.

Coquerel’s sifakas live in social groups of between three and 10 individuals, and the age and sex composition of the groups vary widely. Females are dominant to males, which gives them preferential access to food and their choice of mate.

A home range of between 10 and 22 acres is maintained by wild groups. However, within this area, a core territory of five to eight acres is utilized over 60% of the time.

As of 2018, Coquerel’s sifakas are classified as critically endangered in Madagascar and are threatened with increasing habitat destruction and the erosion of social customs against hunting this species. Learn more about the new IUCN Conservation Assessment for this species and others here.

The species is found only in the Ankarafantsika Nature Reserve and the Bora Special Reserve, and these dry, deciduous forests have both been damaged by yearly fires set by nearby farmers. Hunting of these animals by locals might occur in some areas, although in many parts of its range it is protected by taboo or fady.

The DLC is located on 100 acres in Duke Forest and is famous for its Natural Habitat Enclosures. Here, lemurs free-range in large tracts of forest and live in natural social groups, giving researchers and visitors the opportunity to observe the same behaviors, social structures, and age classes that would be observed in the wild.

Here, a family of four sifakas is caught on trail cam bouncing through their forest home.

Sifakas are featured in episode three of our FREE virtual tour series! In this adventure into the DLC’s Natural Habitat Enclosures, we’ll watch sifaka doing the things they do best—all while learning how we keep lemurs safe and healthy in their forested areas. Take a walk on the wild side with Pompeia, Francesca, and a couple of photobombing friends!

Me and You and Zoboomafoo is a feature-length video adventure—created by the Duke Lemur Center in celebration of World Lemur Day on October 30, 2020—co-hosted by Duke alumnus Martin Kratt, co-creator of Zoboomafoo and Wild Kratts! Through Martin’s story and so many others, Me and You and Zoboomafoo explores how one place, nestled in the forests surrounding the Duke University campus, can inspire a whole world of impact.

Martin shares stories of how his experience at the Lemur Center took him from being a Duke undergrad to an Emmy Award winner who’s introduced generations of children to lemurs and wildlife conservation. Of course, the film features LOTS of behind-the-scenes footage of the DLC’s lemurs, too, and even some retro Zoboomafoo!

If you’ve ever been curious about how we train the lemurs to voluntarily come in from their Natural Habitat Enclosures (NHEs), then check out this behind-the-scenes video! Lemur caretaker Melanie Currie calls to Coquerel’s sifaka mother/daughter duo Pompeia and Francesca using their auditory cue (two short whistle bursts) and a little extra verbal encouragement: "Come on, Pom Pom!" Pompeia and Francesca leap right into a self-contained fenced area within the larger NHE, to enjoy their meal.

To provide an extra reward for their voluntary cooperation, all free-ranging Coquerel’s sifakas receive their favorite food—shelled peanuts—on their “lock-up days” twice a week over the warmer months. You can see that Francesca barely reacts to Melanie shutting the doors—she's far too busy with her peanuts! Don’t worry, after they finished their meals, Melanie opened the doors so that Pompeia and Francesca could continue enjoying the forest!

Send a lemur a present: You can send special treats to the DLC’s lemurs, as well as raw materials for us to construct special enrichment activities to keep them happy and healthy. Simply visit our amazon.com wishlist! In the image above, Pompeia's daughters, Francesca and Isabella, enjoy their new interactive feeders gifted to them from the wishlist - so fun!

Adopt a Coquerel's sifaka: Want to learn more about this species AND help support their care, not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Pompeia, a female sifaka, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur program! Adoption packages start at just $50.

Visit the Duke Lemur Center: The DLC is only partially funded by Duke, so we rely heavily on revenue from tours to help pay for lemur care and housing as well as our conservation work in Madagascar. So, something as simple and fun as visiting the Lemur Center—either virtually or in person—can help us help the lemurs!

Engage in conservation locally: Though it doesn't directly affect lemurs, the DLC also promotes local conservation. We encourage visitors to support local ecosystems and protect local habitats, similar to the way we're helping the local people in Madagascar preserve lemurs' natural habitat. A fun way to do this is to plant a local pollinators garden at your home or school. The DLC itself is incorporating a Monarch Waystation into its landscaping for the summer tour path in 2017. You can also stop using dangerous chemicals on your lawn, which might end up in lakes and streams and harm fish, frogs, and other animals.